The Austin Chicano Huelga: Making East Austin Historic

BY MATTHEW MEDINA

February 6, 2024 marks the 53rd anniversary of Cesar Chavez’s visit to Austin in support of the Austin Chicano Huelga, a Mexican American-led labor movement sparked by the Economy Furniture Industries strike of the late 1960s/early 1970s. In honor of this anniversary, this four-part blog series on the Austin Chicano Huelga was prepared by Fowler Family Underrepresented Heritage Intern Matthew Medina. Read the series here.

ECONOMY FURNITURE STRIKE URBAN HIKE | SATURDAY, JUNE 15 | 8 AM - 11 AM

Join us for a walking tour of the sites and places of the Economy Furniture Strike, one of the most significant labor actions by Mexican Americans in Austin’s history. This 2-mile urban hike will be hosted by Preservation Austin’s Fowler Family Intern, Matthew Medina. Info and tickets HERE.

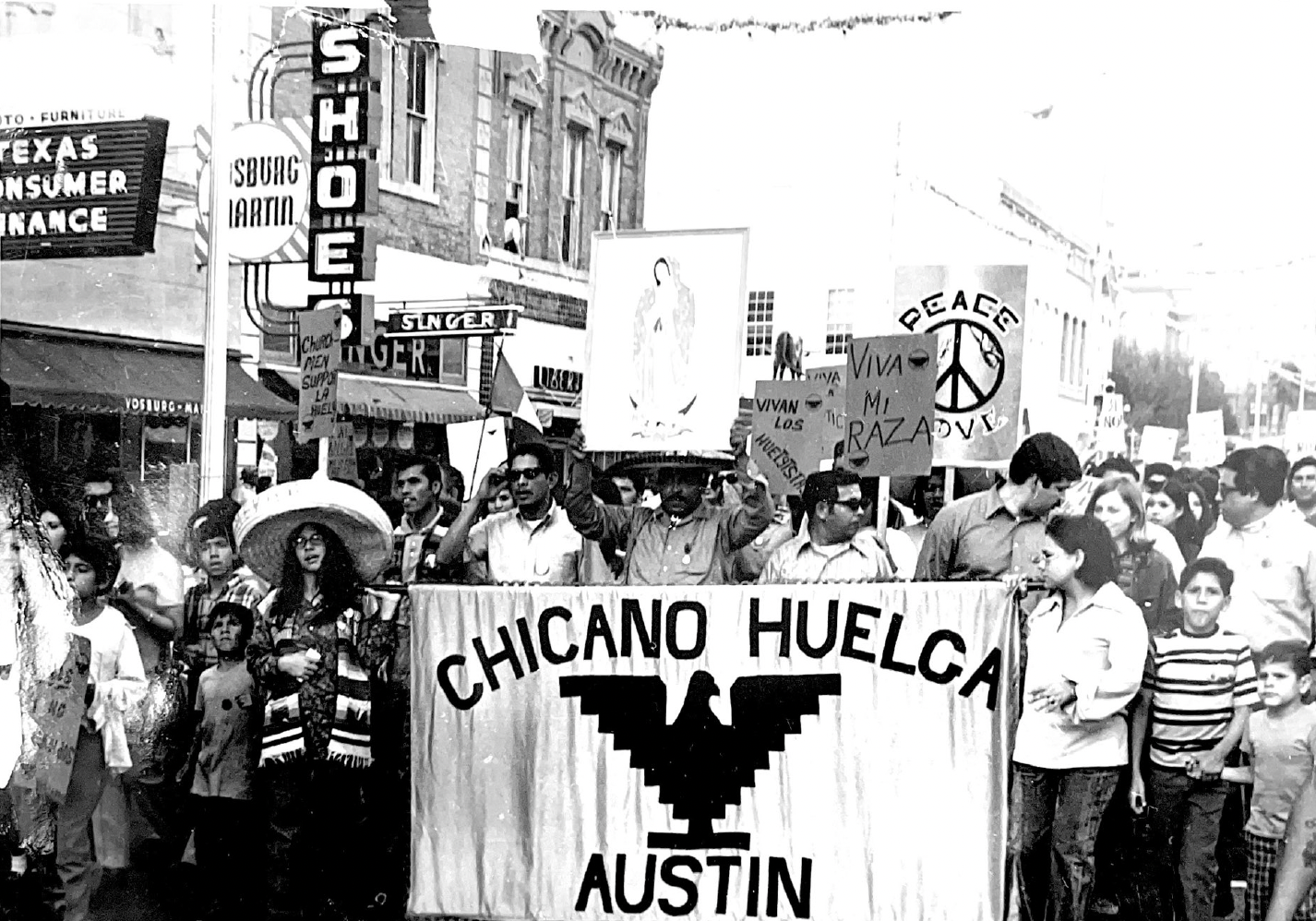

Economy Furniture strikers marching on Congress Ave, 1969

VICTORIA EN LA LUCHA

The summer of 2023 has etched itself into American history as union members around the country inspired a fervent new labor movement, demanding respect and change. Austin has a rich history of labor organizing, activism, and grassroots movements. East Austin was the setting for a movement talked about too little – a two-and-a-half-year-long labor strike by the overwhelming majority Mexican American workforce of the Economy Furniture Industries plant at 9315 Old McNeil Road in North Austin.

The workforce demographic was shaped mainly by the plant's previous location in East Austin on the corner of 5th Street and Shady Lane, which housed the upholstery efforts of EFI for over 20 years before relocating the workforce north. An Austin American-Statesman article celebrating Economy Furniture's 40th anniversary chronicles the company’s move to the larger plant in June of 1964. "Growth Machine," a podcast by KUT-KUTX Austin, sheds light on the history of segregation that has shaped city demographics, and provides an understanding of why this East Austin factory had so many Mexican Americans working for them. The podcast cites the infamous 1928 city plan as a driving force for segregating Mexican and African American communities into East Austin. It adds that this same plan designated East Austin as an industrial district, which historically contextualizes the presence of the EFI plant in East Austin.

Economy Furniture’s manufacturing capabilities were built over the years through the skilled and dependable labor of many Mexican Americans; however, the workforce did not benefit much from their efforts. Tensions started to boil as many workers had only received nominal wage increases over a \decade or more with the company. The workers realized the only way their concerns would be heard was through a union, which was certified by the NLRB in October of 1968 after 90% of the workforce voted in favor of a union representation. Unfortunately, management at EFI refused to recognize their union vote and the decision by the NLRB, which prompted workers to “put down their tools in exchange for picket signs” on November 27th, 1968. The strike, which became a catalyst for the city’s Chicano movement of the 1970s, became known as the Austin Chicano Huelga. The effort was successful and led to the recognition of the UIU Local 456, a signed Collective Bargaining Agreement, and back-pay for the striking workers, "Huelgalistas," in September of 1971.

LA COMUNIDAD

Strikers and students at Austin Chicano Huelga meeting at St. Julia, 1970

The Austin Chicano Huelga was a community effort. The struggle of Local 456 and the image of Chicanas and Chicanos marching the streets inspired an awakening in the Hispanic population of Austin. Catholic Churches in East Austin provided foundational meeting spaces for early organizing efforts and throughout the strike. Economy Furniture workers held a meeting to discuss the decision to go on strike in the Fellowship Hall of Cristo Rey Catholic Church on November 21, 1968. Organizational meetings were held periodically throughout the prolonged strike at Santa Julia Catholic Church and Cristo Rey Catholic Church. Many of these meetings, one depicted by a grainy photograph, happened before mass demonstrations, ensuring successful rallies and marches.

Cesar Chavez and Father Joe Znotas, 1971

Local heroes Father Joe Znotas, pictured with Cesar Chavez, from Santa Julia and Father Dan Villanueva from Cristo Rey were active in the movement, on picket lines and speaking at rallies. Student activist organizing during the 1960s and 1970s formed a symbiotic relationship with the Economy Furniture strikers. Lencho Hernandez, a strike leader and official “Boycott Coordinator,” is pictured visiting student boycott efforts on the UT campus. The Rag, a University of Texas student-led periodical focused on Austin's radical counterculture, covered the strike throughout its duration. Their comprehensive coverage of the strike kept UT students involved and amplified coverage from East Austin publications, while the established Austin news media would not report on any aspects of the strike.

The labor organizing of the Austin Chicano Huelga catalyzed civic engagement in local politics for many of the striking workers. "When [Richard] Moya ran in the primary for Country Commissioner, Place Four, the [Economy Furniture] strikers were active in their support." writes a Rag reporter. Local political legends Senator Gonzalo Barrientos, Commissioner Richard Moya, and Mayor Gus Garcia all recount their experience of the Austin Chicano Huelga in a production by Austin PBS "El Despertar," in which they explain the strikes' importance to the growing civic action of Chicanos in Austin. They were also beneficiaries of the organized support provided by Huelgalistas early in their political careers. Richard Moya was a regular speaker at the many rallies held by and for strikers.

Strike organizers meeting with UT student supporters, 1970

The many aspects of the strike, including rally organizing, handbill passing, picketing, and boycotting, were an introduction into active civic engagement for many people in East Austin. Various iterations of rally flyers distributed throughout the entire strike feature many local and national Chicano Movement leaders. The first major "unity rally" organized by the Economy Furniture Strikers on November 30, 1969 featured speeches by national Chicano icons like Corky Gonzalez and Hector P. Garcia. The demonstration included an organizational meeting at Santa Julia, and a “car rally in the Barrio.” One could only imagine the inspiring spectacle of low riders, students, strikers, and activists.

The most crucial rally came in 1971, when Cesar Chavez was finally able to make an appearance to show solidarity with the Huelgalistas. [Picture 5] The Economy Furniture Strikers had built a well-organized machine of labor activism by the time of Chavez's arrival, officially organizing as the "Austin Chicano Huelga Committee" headquartered at 1915 E 1st Street. Their 12-month operating budget for 1971 laid out the plan for a massive statewide boycott effort involving over 20 different community partners from Texas cities between El Paso and Houston, a public information campaign, and coordinated student efforts from Texas universities. The visit by Chavez had been in the making for a long time, and sometimes engulfs the history of the Economy Furniture Strike; however, a speech delivered by Chavez to the Huelgalistas and supporters of the strike asserts the importance of the effort in Austin, "They're setting the stage for wide organizations…not only in Texas but many other states around Texas."

Cesar Chavez’s appearance at the 1971 rally

LAS CHICANAS

A photo of women in what appears to be the Austin Chicano Huelga Office shows some of the underrepresented heroes of the Huelga. In her master's thesis titled "Austin Chicano Huelga," Mary Elizabeth Riley adds the role of women into the history of the strike, arguing that they were placed in a unique role as striking women and keepers of their home, often working a "double day." The contributions of the Chicana rank and file often go overlooked; as Riley explains, much of the little news coverage available on the strike tended to feature the Chicano leaders of the strike much more. Although left out of the record, the efforts of these valiant women offered a stark contrast to the historical relegation of Chicanas to more domestic spaces. Like their male counterparts, the Chicana Huelgalistas fought for economic viability against Economy Furniture's predatory pay practices; however, it is also essential to highlight the burden of traditional gender roles in order to understand the precarious situation the women of the labor movement were placed in.

Women of the Austin Chicano Huelga movement

VAMOS ADELANTE AUSTIN

A documentary released in 2010 by ACC’s Center for Public Policy and Political Studies, “The Economy Furniture Strike” narrated by Dan Rather, beautifully visualizes and narrates the history of the strike. The film preserved the public memory of the strike, there for anyone to view with a quick search on YouTube, but what about the physical memory?

Site of the former Austin Chicano Huelga offices in East Austin, 2023

(Photo: Matthew Medina)

There is an empty lot on the corner of E. Cesar Chavez and Lynn Street where the Austin Chicano Huelga office once stood as a pillar of community activism. It disappearance unnoticed, just another building erased by time and fading memory. Like the office, many structures that absorbed the history of the Austin Chicano Huelga are gone, but remnants of the old East Austin fabric remain, hiding behind new facades and overgrowth. At 1619 E Cesar Chavez stands Flat Track Coffee and Bike Shop (which makes excellent horchata) there used to be the East First Neighborhood Center, once a hub for the many Mexican American politicians and people who supported and received support from the Economy Furniture Strikers.

Hiding on the corner of 5th Street and Shady Lane stands the Art Deco exterior of what used to be the Economy Furniture Manufacturing Plant, covered by weeds and bushes slowly baking in a record Texas summer heat wave. Although it was not the factory that the strikers would picket at, the building provides a direct connection to the history of the workforce. Other pillars remain standing, changing, and growing with the needs of an evolving community. Santa Julia and Cristo Rey Catholic Churches still serve East Austin with the same welcome of the 1970s. What happens to this story? As the endless need for progress engulfs East Austin, how often are we thinking about and advocating for preserving the spaces that make the alluring neighborhood so radical and historic? The time and the need for preservation is now, Adelante Austin!

The Economy Furniture Manufacturing plant in East Austin, 2023 (Matthew Medina)

Matthew Madina is one of Preservation Austin’s 2023 Fowler Family Foundation Underrepresented Heritage Interns. He is pursuing a master’s degree in Public History from Texas State University.

All historical pictures courtesy of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection.